PRIMARY CARE

Opioid Use in Non-Palliative Subacute and Chronic Pain

Clinical Guidelines and Resources

Sign up for Figure 1 and be notified directly of new clinical cases and related research, CME activities, quizzes, news, and trends. It’s free!

Figure 1, 2, 3

Non-opioid therapies are preferred in subacute/chronic pain management due to better safety profile and increased efficacy for specific conditions

If risks of continuing opioids outweigh benefits, a gradual taper while optimizing other modalities is safer and more effective than rapid discontinuation

Risks versus benefits should be frequently reevaluated with any dose or medication change, and patients should be counseled on risk mitigation

Summary

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) updated their opioid prescribing guidelines in 2022 as part of a response to the ongoing opioid crisis. This summary focuses on their recommendations for outpatient management of subacute (lasting one to three months) and chronic (lasting longer than three months) pain in adults, excluding those with sickle cell anemia, cancer, and palliative or terminal conditions. Getting a thorough history of the pain, including prior treatments, comorbidities, and potential contraindications, is key in selecting the right medication for each individual patient.

Opioid Use in Non-Palliative Subacute and Chronic Pain Clinical Guidelines and Resources

When deciding whether to initiate opioids for management of subacute or chronic pain, clinicians should first consider possible alternatives. Non-opioid medications such as oral or topical NSAIDs and acetaminophen for arthritis; SNRIs, tricyclics, and gabapentinoids for neuropathic pain; and disease-specific therapies such as migraine prophylaxis are more effective than opioids for many pain types. Non-pharmacologic options including physical therapy, acupuncture, spinal manipulation, and cognitive behavioral therapy are also effective tools. Procedures like joint injections or replacements may be useful for localized pain. In the absence of contraindications, these can be used in combination with opioids to minimize necessary dose. Unfortunately, cost and accessibility must also be taken into consideration when recommending non-pharmacologic therapies.

The need for opioids should be regularly re-evaluated in patients with subacute and chronic pain. Setting concrete functional goals such as being able to travel or return to work can be helpful in evaluating treatment efficacy, appropriate dosing, and boundary setting. When the risks of continuing opioids are felt to be higher than benefits, providers should work closely with patients on a taper plan. Pausing or stopping at a lower dose rather than full discontinuation may be necessary. Non-collaborative/unilateral tapers or rapid discontinuation are discouraged unless there are warning signs of imminent overdose, as they are unlikely to be successful and may cause harm. The greatest risk of overdose is actually during taper or soon after discontinuation. All patients who are prescribed opioids should also be educated about and prescribed naloxone, a potentially life saving reversal agent, in case of overdose.

Patients with chronic pain who have been on opioids for over a year benefit from an especially slow taper of 10% a month or less to avoid inducing withdrawal. During the taper, patients must be supported through non-opioid and behavioral interventions, as well. Depression and anxiety are common and may interfere with patients’ willingness to taper. Other medications may be useful in mediating withdrawal symptoms, although avoiding withdrawal altogether is preferred.

Regular drug testing for prescription and non-prescription medications may be useful when evaluating risk of overdose, but should be implemented for all patients receiving opioids, not just those who appear to be “high risk.” Toxicology results should not be used to automatically dismiss patients from care, but rather trigger a conversation about the need for additional support or different prescribing methods (e.g., weekly as opposed to monthly). Clinicians utilizing tests should be aware of their limitations, including difficulty detecting synthetic compounds.

Full Guidelines

Read the full guidelines on prescribing opioids for pain from the CDC: CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain

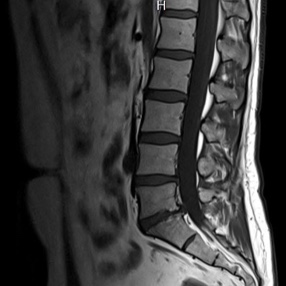

Patient Cases

Click on the image to see the full case details and sign in to view community comments.

See more cases like these

Sign up for Figure 1 and gain access to a library of 100,000+ real-world cases.

Related Research

New Approaches in Drug Dependence: Opioids | PubMed

“This article aims to provide an overview of standard and adjunctive treatment options in opioid dependence in consideration of therapy-refractory courses. The relevance of oral opioid substitution treatment (OST) and measures of harm reduction as well as heroin-assisted therapies are discussed alongside non-pharmacological approaches.”

Primary Care Management of Long-Term Opioid Therapy | PubMed

“The United States underwent massive expansion in opioid prescribing from 1990–2010, followed by opioid stewardship initiatives and reduced prescribing. Opioids are no longer considered first-line therapy for most chronic pain conditions and clinicians should first seek alternatives in most circumstances. Patients who have been treated with opioids long-term should be managed differently, sometimes even continued on opioids due to physiologic changes wrought by long-term opioid therapy and documented risks of discontinuation.”

Related Medical Calculators

DIRE Score for Opioid Treatment

Kaci McCleary, MD

Hospice and Palliative Care Fellow, OhioHealth