Dr. Scott Weingart is one of the founders of the free, open-access medical education movement. He spoke with Figure 1 co-founder Dr. Joshua Landy about FOAM, emergency medicine, critical care, the future of academic publishing, and on-call snacking. Dr. Landy presented Dr. Weingart with a series of questions asked by the Figure 1 community as well as some of his own questions. What follows are the highlights of their conversation on healthcare burnout as well as the complete edited transcript of their conversation.

Heroes of FOAM

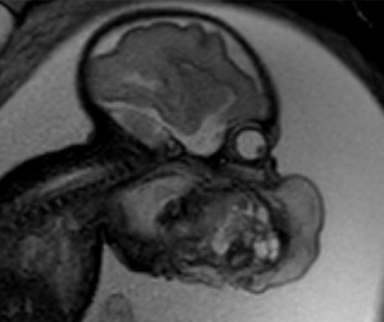

Name: Dr. Scott Weingart

Specialty: Resuscitation & Emergency Department Critical Care

Motto: Attempting to Bring Upstairs Care, Downstairs One Podcast at a Time

Why FOAM? “FOAM allows you to discuss clinical experience in areas where evidence doesn’t exist or in areas where evidence may send you to a path of confusion.”

Where to find him: On the EMCrit site, on the EMCrit Twitter, but as audio is his preferred format, on the EMCrit podcast. (With more than 19 million downloads, you’ll be in good company.)

Favorite on-call snack: “I have some strong feelings about this. Beef jerky or some kind of high protein thing because I don’t think you should be eating anything enjoyable and high carb on shift because your stress hormones will just turn into fat.”

Favorite intubation technique: “I don’t have a favourite, it depends on the individual patient, but if you forced me to have one it would be the one I created, the delayed sequence intubation.”

Favorite ventilator: “I am a strong strong fan of the Evita by Drager, the highest of the line that’s available at any given moment. That’s a bias because I am an airway pressure release ventilation fan, and I think the Dragers have the best valves in the industry.”

Favorite attending as a learner: During my fellowship the head of the Shock Trauma centre in Maryland, who I think delivers the best trauma care in the world, Thomas Scalea. He is my hero, my mentor, the person that I hope I can have some portion of his greatness at some point in my career.

On FOAM and Academic Publishing

Dr. Joshua Landy

Let’s dive in. First of all, I wanted to tell you that the healthcare professionals on Figure 1 — and me in particular — are fans of yours. I use a lot of your materials when I teach critical care.

The first question is from a paramedic who writes:

“My question has to do with how you see FOAMed becoming incorporated into the traditional medical community who rely solely on literature/studies. Do you think they are on the verge of integration, or perhaps polarizing medical education to two schools of thought, or do you see a little of both in the coming decade? Please be specific”

Dr. Scott Weingart

I think it’s a great question. The first thing I’d say is that we need traditional medical publishing no matter what, that is the sine qua non for all, but the question references FOAM. For anyone in the audience who has no idea what that is, it’s an acronym for Free Open Access Medical Education meaning stuff on the web you get for free or behind a password wall but you don’t have to pay for and with the desire to educate people in medicine, that’s FOAM.

Most of FOAM is built on traditional medical publishing, so it’s never going to be a replacement for it, but the two do work beautifully and synergistically together as long as people are not too busy defending their silos.

You need research, and research should never be published on FOAM. That would be crazy to have an original research topic published on a blog or podcast because there is no peer review, there is no vetting and it doesn’t make a lot of sense. To publish in the traditional journals, but then to actually try and translate to the bedside, to make this usable, to have dissemination, the obvious channel is free open access medical education.

The authors and researchers and scientists that are savvy to this are engaging with these new outlets are calling me up and saying “Hey, I just published this study, it’s right up the alley of EMCrit, can you do a show on it or have me on for an interview?” I say hell yes, because that’s what we do best. It’s taking that work and getting it out there.

The standard dissemination cycle takes like ten years and we can do it in ten minutes. And then what I think my bent is, is trying to figure out is how to take the research and actually make it usable on a clinical ship or on a doc in the trenches of the ICU or an ED.

Dr. Landy

I want to follow up with something that you said which was that it was crazy to publish primary research on a blog because it’s not peer reviewed. Do you think that there is a possibility that there could be a new platform type out there, in the future or potentially out there now, that can expedite peer review and make things available much faster than the current legacy systems of publication?

Dr. Weingart

Yes, but I don’t call that a blog. This is all semantics at some point, but first of all, I don’t think any journals 10 years from now will be publishing a print version for any reason, except to put in libraries, and those libraries should really come to their senses and stop stocking those and they will disappear, too. A bunch of really high level journals are going to online publications only and they look very much like a blog, but my distinction between a blog and a journal is that a journal does have pre-publication peer-review. That may change, but for now, that’s part of my definition. They have an editorial board instead of one person making decisions, and they have the aegis to not put stuff that’s pure opinion unless clearly delineated as such. This is, in my mind, the structural difference between a blog and a journal, even if that journal is online and is using the same WordPress theme as a blog is.

Dr. Landy

I was going to say there was a little blow-up on Twitter recently about a study that was published in The Lancet on the topic of hypertension. It had 24 authors and 21 patients in the study. I feel like this, in itself, represents the fact that we really should be doing a better job.

Dr. Weingart

Yeah, and SMACC had some wonderful panels where they pitted the former editor of the BMJ, who is very forward-thinking, to the editor-in-chief of The New England Journal, who also had some beautiful points to make but maybe a little bit more into the conservative, older style of journal publication. I would highly recommend that anyone interested in this topic check out that panel.

Dr. Landy

One of the things that hit me between the eyes on this topic is the writing style. If you go back and read journals from the 1950s and 60s, their descriptions and their recommendations in writing are just so beautiful, elegant, and descriptive. We have seen that writing style sinks into a very technical, automated, formatted collection of text which can be very harsh to digest. To get this information in the hands of practitioners, writing in a style like yours seems to be the way to go, and on that point, a vascular surgery resident asks on Figure 1:

“Do you think that it’s better to disseminate information through academic channels or through FOAMed social media, etc.? If you could only choose success in one domain, which one would you select?”

Dr. Weingart

Such a good question and I’m going to link it up to the comment that you just made because I think it was particularly incisive. In the old journals from 50 years ago, you were allowed to publish articles on “here was my clinical experience for the last 10 aortic dissections I took care of”, and there’s value to that. It’s not a randomized control trial, but if it’s speaking on a topic of tacit knowledge or of just “here is my clinical practice, I’m regarded as a good clinician, maybe you want to hear what I have to say”– there’s huge value to that. That’s kind of disappeared in traditional journals. There’s no outlet for that, and the new world of social media and FOAM has filled in the gaps to allow you to discuss clinical experience in areas where evidence doesn’t exist or in areas where evidence may send you to a path of confusion. So if I had to choose between traditional publishing and FOAM, then it’s pretty clear for me, I am a FOAM publisher. That’s the stuff I care about. I care about talking evidence, and if there’s no evidence out there then taking the best physiology and applications of clinical experience and trying to make sense of what to do on an actual patient encounter.

On Keeping Up With FOAM

Dr. Landy That leads us to another question:

“Dr. Weingart – thank you for being open to questions on Figure1! You are certainly a subject matter expert and an influence to many in EMS. Do you have any advice regarding how many articles/journals/podcasts we should be reviewing daily to keep fresh? With FOAM, one could spend hours reviewing the latest and greatest”

Dr. Weingart

I did a talk on this and it’s up on the podcast site. It’s called the path to insanity and by the title, you should basically get an idea of what I don’t recommend doing, which is what I do: I try to read every single research study that is even tangentially related to my field of practice, critical care. I just listen to any podcast out there, and any blog post that I try to read. That is not sustainable unless you want to eliminate everything else in your life except for friends, family, and work, which is pretty much what I have done.

I don’t recommend that as a path, but there’s an economic principle called the Pareto Principle. It’s the 80⁄20 rule which applies to most things in life: To get 80% of the benefit it only takes 20% of the effort. It’s that last 10-20% that requires the other 80% of the effort, so you can get almost all of the way there by doing a much more streamlined approach. I cut the 60 journals I read to 12 journals a month. Which, when you think about it, means if you are reading one journal every three days, you are of course not reading a journal cover to cover.

I get a table of contents in my email, and I’ll browse through, see what’s of interest, check out the abstract, and if it still looks interesting, check out the whole article. That’s a very sustainable way to go. Don’t listen to 20 podcasts, listen two or three, make one of them EMCrit if you’re an ED or critical care person (that’s just my personal bias), read a few blogs, but you don’t need to go crazy and be a completionist and try to read everything out there.

Dr. Landy

Not everyone has the appetite or the capacity to be an aggregator, but certainly, everybody should be consuming some of these resources. Can you give us some tips on how to construct reading filters?

Dr. Weingart

I could do it for people that are in the resuscitation world, which is that Venn diagram where critical care and emergency medicine meet. If you were to read EMCrit, that would be a pretty good start, and I’m not saying that because of my stuff. I’m saying that because of the incredible team that we started to gather. Folks like Josh Farkas, who is trolling through every piece of literature in critical care and just doing these amazing blog posts about it. You have Rory Spiegel, reading every piece of emergency medicine literature and doing amazing blog posts about it, and then you have me doing podcasts every couple weeks to fill in the gaps that they’re not hitting, or maybe to really emphasize their work.

If you add to it a blog like Life in the Fast Lane, you’re getting pretty close. And there are two or three others that you can listen to, and you will get most of the way there. I think you should read the major journal of your specialty, so for critical care, you probably should be reading Intensive Care Medicine and Critical Care Medicine and now you get the European approach and the American approach. You could argue to read the Blue Journal as well, the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, which is more pulmonary oriented, but if you read those three you’d be in pretty good shape for whatever was missed by those social media sites. That may be enough.

On Why Emergency Medicine is Broken

Dr. Landy

Great, OK. We’re going to talk a little bit about people’s feelings about emergency medicine, so a Figure 1 member asks:

“Hey Dr. Weingart; I’ve grown disillusioned with EM’s future of-late. It seems the ED’s in my area are focused only on cramming in tests and dispo-ing pt’s as fast as possible. In addition, almost all decisions are deferred to consults and our EM docs perform almost no procedures. I’m worried the EM I’ve loved for the past decade is fading away. Is this a trend you see for most (non-EM/CC) units? And I think you touched on this very nicely at your talk at SMACC in Berlin where you were talking about the end of the paradigm of emergency medicine.”

Dr. Weingart

Yes, and I have to put a disclaimer, I’m not an emergency physician anymore. I haven’t been for years, I only work in an ED intensive care unit. I say this as an outside bystander. I have been an emergency physician for many years, so I think I’m capable of speaking to it, but having the outsider’s view you may add some additional wisdom, who knows, but emergency medicine is broken. It was a great idea at the start of the specialty and now it needs to fix itself and it is 100% not the fault of the emergency physicians because these docs are amazing.

Almost every ED doc I encounter genuinely wants to do the right thing, and when I say the right thing I say that from the perception of the outside services, they are not given the aegis to do so, their job is impossible, and the reason why is that they are expected to take care of patients who aren’t sick to the really negative detriment to the patients that are sick. Getting patients out of the ED, whether than means admitting them as quickly as possible or discharging them as quickly as possible, somehow has taken an overarching level of support above just taking good care of patients.

One of the main things I said in that “EM is broken” talk is a reference that there is no harm to patients who aren’t sick waiting, and yet somehow the government, the regulatory bodies, figured out that there’s huge harm, and we have to get these patients out as quickly as possible. It’s not just a U.S. phenomenon, Great Britain has this, Australia has this, and it’s breaking the specialty. If you could just do right by each patient as you take them with a triage system in which you take the sickest ones first, then everything would work out, but they won’t let ED docs do that.

Dr. Landy

Yes, because of wait times being a key metric.

Dr. Weingart

Yes, wait times and timed decisions. I don’t know if people outside of EM know this, but the time it takes for you to decide to admit a patient is a trackable metric that you’re getting dinged on. If you take extra time to really figure out what’s going on with the patient, you’re gonna get yelled at, and an aggregate, you’re a good doctor, who says I’m not gonna admit this to the hospital until I actually know what’s going on, you are hosed, you will get fired.

Dr. Landy

There’s something about that that is reminiscent of the way that economics are generally skewed in medicine, and that’s why hospitals and health care purchasers can’t be rational buyers. Doctors don’t choose the tools they use. We don’t choose our key performance metrics, we don’t choose the way that we measure whether our job has been a good one or not.

Dr. Weingart

Absolutely, and it all comes back to the contractor’s triangle: Good, quick, or cheap. You can pick two out of the three but you can’t have all three, and people don’t seem to realize this.

If we were allowed to charge patients the same way a restaurant or hotel does, then we would just keep upping the price and no one would wait. Or, you could have it cheap and good, but you can’t have all three, it doesn’t work. It doesn’t work in any domain. I don’t know why people seem to think that medicine is going to be different. You can’t have it good, cheap, and fast.

On Being a Good Emergency Physician

Dr. Landy

Certainly not efficiently. A medical student asks:

“Dr. Weingart, as a medical student I hear EM docs taking flak from other physicians for passing the buck and/or decision making. Granted this isn’t all docs, but it seems significant enough in their perception to mention. Do you see this problem in EM? Is there a viable solution? What keeps good EM docs good, and what bad habits do you see others fall into?”

I know that you’ve written about cognitive biases before, so this might be a nice opportunity to help this student out.

Dr. Weingart

It’s very similar to the concepts we were talking about in the previous question, but a good EM doc knows from the first three minutes of encountering the patient whether they need to be admitted or discharged. With the current system, a lot of times if the answer in their head is “I think this patient needs to be admitted,” it bears a lot of economy of effort just to say “screw it, we’re going to admit him, maybe we’ll send off a whole bunch of tests and then let the hospital figure it out.” Is it what these ED docs want to be doing? No, but that’s what their position is forcing them to do.

I’m lucky enough to have a different gig. We have a separate area that’s only for critically ill patients, coming to the emergency department or as transfers from other hospitals. We have staff, we have one nurse for every two patients, we have enough docs to be able to figure out what the hell is going on with the patient, figure out what the best ICU for them is, or figure out that the DKA patient with a PH of 6.7 – I know if I work on him for eight hours I could get this patient to the floor. There’s no reason to waste an ICU bed on him, and we’ll keep him, and we’re able to do that. We’re able to take a patient who is 90 years old, end-stage dementia, spend the time, talk to the family, make DNR/DNI comfort care plans and never admit them to the hospital, let them have a good death in the ED. Regular ED docs can’t do that. Their entire department would go to crap, so they’re just juggling 50 or 60 patients at a time trying to keep their head above water and keep anyone from dying.

Dr. Landy

Right, it sounds like you have a scenario in your work life where things work almost exactly where you would have wanted them. You get to look after resuscitation needing patients who have complex illnesses, who’ve come in in emergencies, and you’ve been able to do that outside of being required to do the usual emergency department family medicine type of practice.

Dr. Weingart

Yes, I’m kind of a spoiled brat. I’ve been lucky enough to make my own gig in a lot of ways, both from an academic pathway and a clinical pathway. I count myself as one of the luckiest people out there because I go to work and it’s almost a joke that I get paid for it because I just love it. If you told me all of a sudden, here’s 10 million bucks, I’d still be doing exactly what I’m doing now because I just am the luckiest guy out there.

Dr. Landy

I think some of its luck and some of it probably has to do with the fact that you knew what you wanted, and you helped create the scenario that invites you to do what you want to do at work.

Dr. Weingart

I’m going to go with the luck thing, but thank you, Josh.

On Burnout and How to Avoid It

Dr. Landy

I wonder if you could talk for a moment about how people can take a long term view of their work life, and help work in what is generally considered to be a challenging environment, to create the job that is going to make you want to keep the job, even if you want to win the lottery.

Dr. Weingart

OK, that’s a great question and it’s funny I’m giving a burnout talk to a hospitals group and I’ve been thinking about these issues a lot. So there’s a few things. One is that we get paid very nicely as docs, and you can argue we should get paid more, but for whatever reason when you compare us to most of society, we do okay.

What we give up a lot of the times is time, and that leads to a lot of burnout, but when you really think it through, the tradeoffs may be that a lot of people are happier working 80% and taking 80% of the salary. That’s one real quick path to making yourself a lot happier.

The other thing is that a lot of burnout and misery is just a lack of control. We feel like we’re guided by forces outside ourselves to go places we don’t want to be, but if you think about the problem strategically, you realize you have more control than you think. You can make your most miserable frustrations a project in your hospital and say, “OK, well I’m gonna solve this, I’m gonna go outside the normal path.” Obviously, it’s always easier to say it than to do it, so prove it works and then ask for permission to do it, rather than the other way around.

You can get rid of a lot of frustrations in the job — and actually get rewarded for it — because a lot of the things you’re feeling frustration about, when you fix them, your system becomes more efficient.

Dr. Landy

A part of this, for me, is seeing the joy that people experience in medicine. Because of those little moments of joy, that you did a good thing just then and reflect on that and adopt that and made it part of your daily narrative, I think it probably stands to reason that that sort of cognition is a healthy one, and helps people adopt an attitude in which they can appreciate the work that they’re doing for people.

Dr. Weingart

Absolutely, if you start getting to the point where you’re seeing patients and you’re just miserable, something very bad has happened and it needs to be curtailed at that moment.

If you’re going to work and every single patient is pissing you off, it’s probably not them at that point. One out of 10 I’m happy to blame it on as just an ornery patient, but if every patient is just the worst in the world then you’re probably just burnt out. Bad things are gonna happen in your life and in your relationships unless you really just take a step back and figure out what is going on.

Dr. Landy

So this is Scott Weingart’s official litmus test for burnout: if you hate everybody, it may be time to talk to somebody. Thank you again for your time.

Published July 26, 2021; updated April 26, 2023

Join the Conversation

Register for Figure 1 and be part of a global community of healthcare professionals gaining medical knowledge, securely sharing real patient cases, and improving outcomes.