Summary

After an 8-year-old boy with recurrent episodes of rhabdomyolysis is hospitalized for treatment of a rare inherited disease, his condition quickly deteriorates.

Guest

Jerry Vockley, M.D., Ph.D.

Cleveland Family Endowed Pediatric Research, School of Medicine

Professor of Human Genetics, Graduate School of Public Health

Chief of Genetic and Genomic Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh

Director of the Center for Rare Disease Therapy, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh

Dr. Vockley received his undergraduate degree at Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and received his degree in Medicine and Genetics from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He completed his pediatric residency at the University of Colorado Health Science Center, and his postdoctoral fellowship in Human Genetic and Pediatrics at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. Before assuming his current position in Pittsburgh, Dr. Vockley was Chair of Medical Genetics in the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine.

Dr. Vockley is internationally recognized as a leader in the field of inborn errors of metabolism. His current research focuses on mitochondrial energy metabolism, novel therapies for disorders of fatty acid oxidation and amino acid metabolism, and population genetics of the Plain communities in the United States. He has published ~300 peer reviewed scholarly articles, is the principle investigator on four NIH grants and a co-investigator on 7 others. He has an active clinical research program and participates in and consults on multiple gene therapy trials. Dr. Vockley has served on numerous national and international scientific boards including the Advisory Committee (to the Secretary of Health and Human Services) on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children where he was chair of the technology committee. He is a Founding Fellow of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, and currently serves on its board of directors. He is co-chair of the International Network on Fatty Acid Oxidation Research and Therapy (INFORM). He also serves as chair of the Pennsylvania State Newborn Screening Advisory Committee and the Board of Directors of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. He is a past president of the International Organizing Committee for the International Congress on Inborn Errors of Metabolism and the Society for the Inherited Metabolic Disorders (SIMD), and co-founder and editor of the North American Metabolic Academy.

Transcript

DDx SEASON 3, EPISODE 2

Code blue

RAJ:

This season of DDx is brought to you by Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical corporation.

RAJ:

An 8-year-old boy has recurrent episodes of rhabdomyolysis, a potentially life-threatening syndrome where skeletal muscle fibres break down and leak muscle contents into the bloodstream. The young boy enters the hospital to begin treatment. An echocardiogram shows his heart function is half of what it should be. His condition quickly worsens. A code is called.

SFX [BING]

[VOICE OVER PA] “Code blue, room 305. Code blue, room 305.”

RAJ:

The boy is surrounded by a team of doctors, nurses, and respiratory techs. He’s not breathing. His heart has stopped.

RAJ:

This is DDx, a podcast from Figure 1 about how doctors think. This season is all about rare diseases. I’m Dr. Raj Bhardwaj. Today’s case comes from Dr. Jerry Vockley. Dr. Vockley has been compensated by Figure 1 for his participation in this episode.

Dr. Vockley:

I’m the Chief of Genetic and Genomic Medicine at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. I’m also a professor of human genetics in the Graduate School of Public Health and director program called the Center for Rare Disease Therapy at the Children’s Hospital

RAJ:

This young patient’s journey began years before that traumatic day in the PICU. In fact, it began shortly after birth with reports of hypoglycemia. And a newborn screening that returned a diagnosis of either Long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase, or LCHAD, or, trifunctional protein deficiency. Both are rare conditions that prevent the body from converting certain fats into energy.

Dr. Vockley:

Since you can’t distinguish the two of those, you have to do additional testing, which was done. And the patient was shown to be homozygous for the common tri-functional protein alpha subunit mutation that leads to isolated LCHAD deficiency. The baby was started on frequent feeds to prevent hypoglycemia, including frequently through the night.

RAJ:

That approach seemed to work well to manage his rare genetic condition. The family felt he was developing normally, with good activity and muscle strength. But around the age of seven, he started having recurrent episodes of rhabdomyolysis.

Dr. Vockley:

This is actually pretty common in this disorder. Children can have early symptoms, but if they don’t, oftentimes by the time they hit five or six or thereabouts, will start developing symptoms. We don’t actually know why that happens, but it’s a pretty common finding.

RAJ:

At this point in his life, the child was rarely out of the hospital for more than a couple of weeks at a time.

Dr. Vockley:

So after six or eight months of that, they began to talk to their local metabolic doc about other options for treatment.

RAJ:

The decision is made to refer the patient to Dr. Vockley. By the time the patient arrived in Pittsburgh, he was 8 years old. A recent echocardiogram was normal. But Dr. Vockley had reason for concern: since Long chain fatty acid oxidation disorders (or LC FAOD) lead to a deficiency in mitochondrial energy, a common outcome is cardiomyopathy, a disease that makes it hard for your heart to pump blood. Which can lead to heart failure.

Dr. Vockley:

When I saw him in our research center for his first research visit, I was a little worried because he didn’t seem to me to be all that well. We drew his study blood testing and sent him off for his echocardiogram, which now showed an ejection fraction of about 45% down from the normal 55 to 60% that he would have had six months prior.

RAJ:

Instead of starting treatment as an outpatient, Dr. Vockley decided to admit the child to hospital for closer monitoring of his condition. But as Dr. Vockley was on his way to the hospital the next day, the on-call geneticist paged him to say the child wasn’t looking good and had been transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit.

Dr. Vockley:

By the time I got to the hospital, he was surrounded by a huge team. And I was told that when he got to the PICU he had had a cardiac arrest. His echo at that time showed essentially no heart function. He was not effectively pumping any blood. And so they proceeded to do a full cardio-respiratory resuscitation on him.

RAJ:

Thankfully, the team is able to restart his heart, but his ejection fraction was still almost zero: his heart was hardly pumping any blood. An emergency decision was made to put him on on ECMO – ExtraCorporeal Membrane Oxygenation – sometimes called a “heart-lung machine”

The machine kept him alive for almost 2 weeks.

Dr. Vockley:

Throughout that time, he kept having a test of his cardiac function, and the family and I was told that he really showed no signs of his heart improving. And that there was essentially no blood movement coming from his heart. After about two weeks, the cardiologists had a conversation with us that said there really was very little chance that his heart was going to recover if it hadn’t already recovered. And that now the risks of complications related to ECMO were starting to get quite high. They suggested that we start thinking about withdrawing support and making arrangements for palliative care.

RAJ:

After years of worry and pain, the family had been told their child was going to die. But Dr. Vockley hadn’t given up. He wanted to try a different approach. Over the next few weeks, the patient’s heart functions returned to near normal and he was discharged into rehabilitation for intensive physical therapy. Which allowed him to build his strength back up quickly.

Dr. Vockley:

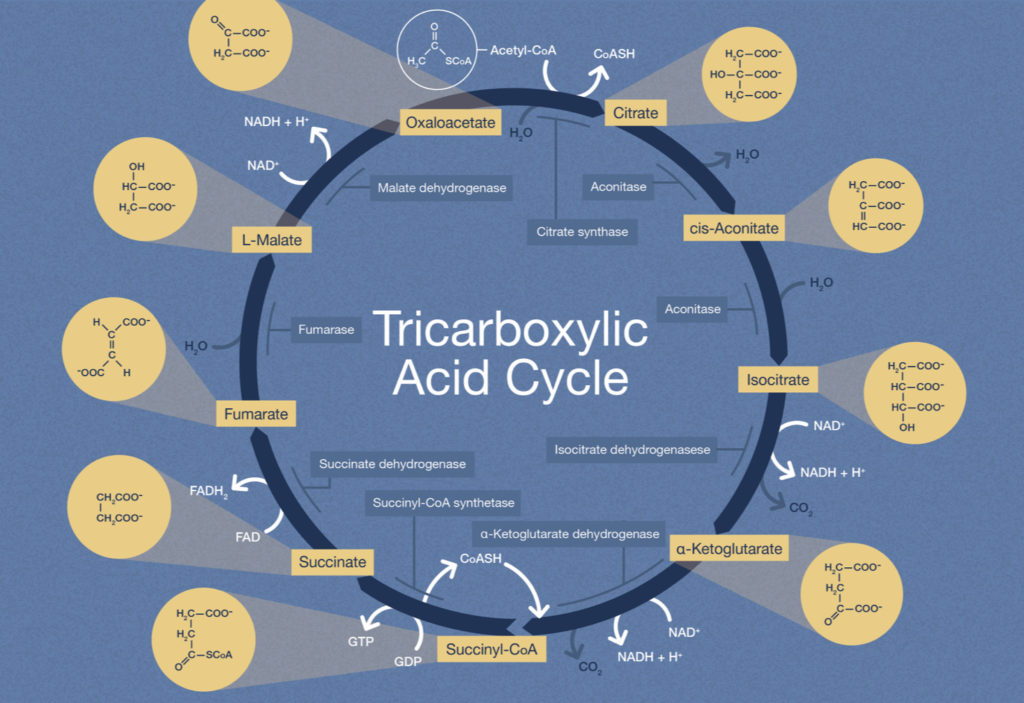

It turns out that because of the block in long-chain fatty acid oxidation disorders, these patients are relying on their TCA cycle or their Kreb cycle to generate energy.

RAJ:

Remember the Kreb’s Cycle, that you learned (probably many times) in school? It’s okay – I don’t either. But understanding it is the key to understanding metabolic disorders.

Dr. Vockley:

So what happens is, as these patients get older, and they have more body mass, or they have some metabolic stress, suddenly they’re no longer generating enough energy and they need additional propionyl-CoA, three carbon units in addition to the two carbon units and suddenly their whole cellular bioenergetics crash.

RAJ:

Your body is a finely-tuned machine, and if it can’t burn fuel properly, it doesn’t perform well.

Dr. Vockley:

This young man did well. He survived his acute episode.

RAJ:

In the world of genetics, a new disease is identified almost every day. What can health practitioners do to try to keep up with this rapidly changing field?

Dr. Vockley:

The most important aspect of this is that because genetic disorders can affect essentially any body system, if you’ve got a patient that is doing something that you just don’t understand, it’s a good idea to get that patient to a genetic specialist who can evaluate for one of these disorders and try to sort things out sooner rather than later.

RAJ:

And finally, you may have heard about genetic therapy, the idea of rewriting genetic code to stop these diseases before they even happen.

Dr. Vockley:

The good news is it’s actually happening now that there are gene therapy trials that are currently in clinical trials. And so the future for genetic disorders is really suddenly here. The idea that we’ll be able to use gene therapy delivery of a new gene, or a new therapy called CRISPR, which has made a lot of publicity lately to actually go in and fix the mistakes in a patient’s DNA are realities. Their realities for a small number of disorders still yet, but the technology is finally robust enough that we’ll be seeing a lot of these therapies coming down the road in the coming years.

RAJ:

Thanks to Dr. Vockley for speaking with us. This is DDx, a podcast by Figure 1. Figure 1 is an app that lets doctors share clinical images and knowledge about difficult to diagnose cases. I’m Dr. Raj Bhardwaj, host and story editor of DDx. You can follow me on Twitter at Raj Bhardwaj MD. Head over to figure one dot com slash ddx, where you can find full show notes, photos and speaker bios. This episode was brought to you by Ulttragenyx Pharmaceutical Corporation. Thanks for listening.